Thursday, February 8th, 2018

Dada Africa, Non-Western Sources and Influences

By Tom Reeves

In May 1915, when Europe was in the throes of the First World War, a young man and his girlfriend made their way to the neutral territory of Switzerland, where, in 1916, they opened a cabaret and founded a movement that would change the face of art forever.

The young man was Hugo Ball, a German poet, who had tried to enroll in the German army but was refused for medical reasons. His girlfriend was Emmy Hemmings, a Germen cabaret performer. Together they opened a nightspot in Zurich that they called Cabaret Voltaire and on February 2, 1916, they issued a press release inviting other artists to join them.

Hugo Ball's Appearance in the Cabaret Voltaire 1916

Photographer: unknown

Image in public domain

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Among the many who came forth was Tristan Tzara, a Romanian poet who would later claim that it was he who founded the artistic movement called “Dada” that emerged from this experience.

The artists and performers gave nightly cabaret concerts of music, singing, dancing, and poetry and created works of art that they displayed on the walls. The cabaret attracted an audience that responded enthusiastically to the raucous, bizarre performances on stage. It operated at almost full capacity for five months before closing.

On July 14, 1916, Ball issued a manifesto declaring that he would read poems that dispensed with traditional language. Dressed as a bishop, he appeared onstage and recited verse consisting of vowels and nonsensical words:

Gadji Beri Bimba

gadji beri bimba

glandridi lauli lonni cadori

gadjama bim beri glassala

glandridi glassala tuffm i zimbrabim

blassa glassasla tuffm i zimbrabim...

The point of his presentation was to strip language to a primitive level — the level at which humans were thought to have once lived in an uncorrupted, childlike state of existence. Returning to that point became the goal of the Dada movement.

The Dadaists sought out representations of the art of tribal peoples of Africa, Oceana, and the Americas, believing that those people were already living in a primordial state of existence. African masks were especially prized because the faces were portrayed in stark geometrical form. The Dadaists incorporated the facial representations into their art. For example, Romanian artist Marcel Janco created African-inspired masks from paper, horsehair, and wire for the performers to wear onstage. Ball reported that as soon as the performers donned the masks, they began moving in bizarre ways that “bordered on dementia.”

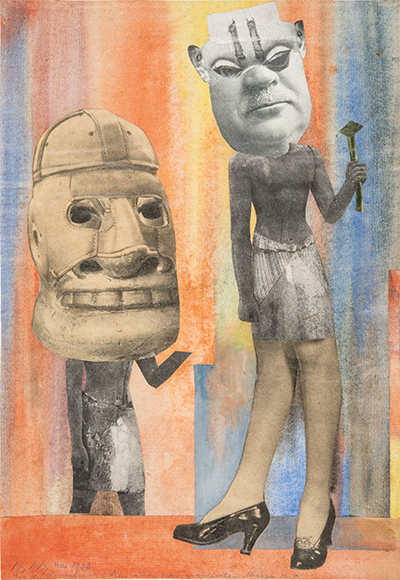

Hannah Höch (1889-1978)

Aus der Sammlung: Aus einem Ethnographischen Museum Nr. IX., 1929

Collage et aquarelle sur papier marouflé

27.6 x 19 cm

Paris, Galerie Natalie Seroussi

© Galerie Natalie Seroussi

© Adagp, Paris 2017

Other examples of Dadaist artists who incorporated African and other tribal art into their art are Hanna Höch, a German, who was a calligrapher and designer, and Sophie Taeuber, a Swiss, who was a painter and sculptor. Höch used cutouts to create phantasmagorical images of half-human creatures posing, dancing, or moving across surreal landscapes. Taeuber created puppets and costumes and later, in 1918, created wooden marionettes inspired by Hopi Indian dolls.

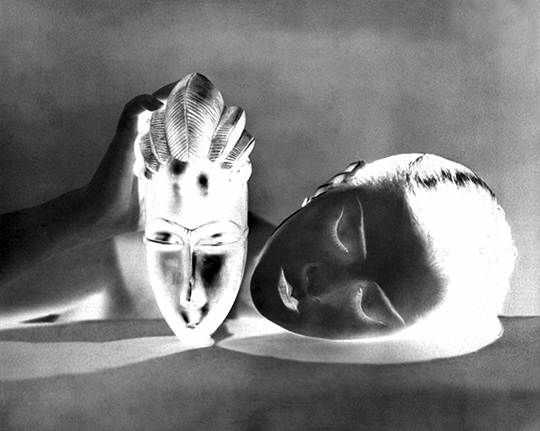

Cabaret Voltaire closed in 1916, but the influence of its artistic agitation spread to other parts of Europe. The Dada movement was strong in Paris, where followers included American photographer and painter Man Ray. Ray produced curious sculptures in the Dada canon and, after the movement ended, he created photographs that portrayed an African mask in juxtaposition with the face of his model and girlfriend Kiki (Alice Prin).

Man Ray (1890-1976)

Noire et blanche, 1926

Epreuve gélatino-argentique négative sur papier non baryté

21 × 27.5 cm

Paris, Centre Pompidou, musée national d'Art moderne

© Man Ray Trust

© Adagp, Paris, 2017

Cliché: Adagp Image Bank

The Dada movement ended in 1922, when prominent members followed French writer and poet André Breton into a new movement called Surrealism.

The exhibition Dada Africa, Non-Western Sources and Influences at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris displays photographs, paintings, collages, puppets, bead work, fabrics, video, sculptures, audio recordings, books, magazines, and letters that document the abundance of art produced during the few years of the movement’s existence. Included are several African sculptures that are displayed next to the Dada works they inspired.

Works by Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga and South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga are on display in conjunction with this exhibition.

Otobung Nkanga (1974-)

In Pursuit of Bling: The Transformation, 2014

Tapestry

182x180 cm

Galerie In Situ - Fabienne Leclerc, Paris

© Otobung Nkanga

Photograph by Entrée to Black Paris

Dada Africa runs until February 19, 2018. The museum is open from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. six days a week (closed on Tuesdays). Admission fees: 9€ full rate, 6.50€ reduced rate. Metro stop: Place de la Concorde. Additional information is available at the following link: http://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/event/dada-africa-non-western-sources-and-influences.

Header Image:

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943)

Motifs abstraits (masques), 1917 - detail

Gouache sur papier

34 x 24 cm

Remagen-Rolandswerth/Berlin, Stiftung Arp e.V.

© Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth

Wolfgang Morell

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!