Thursday, August 23rd, 2018

Gertrude Stein and the Black Narrative

by Sekai Abeni

Image: Left – Richard Wright by Carl Van Vechten (1939); Right – Gertrude Stein by Carl Van Vechten (1934)

The relationship between Richard Wright and Gertrude Stein is one of the many subjects discussed during Entrée to Black Paris’ “Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden” walking tour.

One of Sekai Abeni’s assignments as the Wells International Foundation’s 2018 Summer Intern was to review Gertrude Stein’s novella, “Melanctha: Each One as She May,” and comment upon the fact that Richard Wright was strongly impressed by the speech patterns of Stein’s black characters in this story. The following is her opinion piece about this topic.

Stories written about Black people by White people have dominated the Black narrative in the United States since the beginning of Black people’s arrival in the stolen land. While Black people have always been intellectually capable of controlling their own stories, they have been cut off from education and access to resources that allow them to do so consistently and effectively.

So, when Black Americans, enslaved and freed, began to pen their experience, and their writings found their way into wider circulation, White people were faced with the actual voices of people rather than caricatures. This forced them, to some extent, to face the truth of their oppression.

As Black people have become the authors of their own narratives and the depiction of Black people has evolved beyond (insert any number of stereotypes here), the narratives of White people, often underscored by their own racism, have less and less frequently become front runners in the collective understanding of Blackness.

The Harlem Renaissance gave birth to a new generation of authors whose narratives were no longer focused on pleading for dignity, but rather on writing about the daily lives of Black people. The subject’s race was no longer the central issue. As a reflection of the actual lives of Black people, sexuality, class, reputation, and most importantly, individuality, were addressed in these narratives alongside race.

While examining the drastic change in Black writing during the early 1900s, it is also significant that many White authors of the time took an interest into the work of Black authors. It is said that F. Scott Fitzgerald was a fan of Harlem Renaissance writing. And there is a theory that the main character in The Great Gatsby, Jay Gatsby, is actually a White-passing Black man. The story of White-passing Black people was a popular narrative of the time, and the structure of Fitzgerald's character, Gatsby, calls upon this formula.

When Gertrude Stein wrote “Melanctha”* as part of her book entitled Three Lives, Richard Wright could not believe that she was able to capture the voices of Black people so truly. He found her novella a to be a ground-breaking point in his own artistry. And while by today’s standards, the story relies on some outdated notions and formulas for creating the language and voice of Blackness, in the context of the writing circulating in Black circles, it rings true to an experience many other White authors of the time were not able to capture.

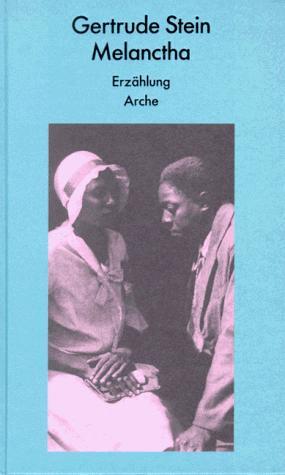

Cover for the short story, "Melanctha"

Cover for the short story, "Melanctha"

Stein's “Melanctha” has been considered the first novella depicting Black life by a White author that steers clear of racial stereotypes and depicts the characters as more than tools for the story and White characters to rely on. She is most notably successful in two realms that lend to the story’s credibility. First, she was able to discuss the concept of colorism with a profound understanding of its everyday effect on Black life, while also staying away from stereotypes. Additionally, she was able to capture the use of language in the different areas in Black life, playing with the class system in which Blackness fluctuates.

These two things may not seem so monumental today. But in a time where the depiction of Black people relied on dangerous stereotypes, it is a feat that Stein was able to create her characters in the way she did.

And while her work on "Melanctha" is profound, it is interesting that Stein didn’t spend that much time, if any in Black communities. Though she entertained and had some Black artists and intellectuals in her circle, she never immersed herself in Black life.

I find that Stein’s work relied on the writing of Black people. She was a great reader and consumer of art and her understanding of the characters and functions of society came directly from the literary culture of the day. I found “Melanctha” to be an interesting portrait of a Black woman’s life. But for me, the work of Black authors of the time, male and female, holds a light to the experience of Blackness with which Stein’s cannot compete.

*Melanctha is the daughter of a black father and mixed-race mother in the novella of the same name. The novella is set in the fictional, segregated town of Bridgeport.

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!