Thursday, October 24th, 2019

Remembering Ed Clark

Ed Clark passed away on October 18, 2019. He was a pioneering abstract artist of the 20th and 21st centuries.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Ed on several occasions, talking with him about his life and experiences as an artist as well as his relationship with friend and fellow artist, Beauford Delaney. I published articles about him in the Entrée to Black Paris blog in 2010 and 2016. I've combined the content of these posts and republished them here in celebration of Ed's life and work.

********

Montparnasse is world renown for an artistic tradition and a Bohemian lifestyle that began in the 1900s. That tradition was still alive and well when more than 200 African-American soldiers took advantage of the GI bill after World War II and streamed into Paris. Among them was Ed Clark, one of the most successful African-American artists to live in Montparnasse and study there.

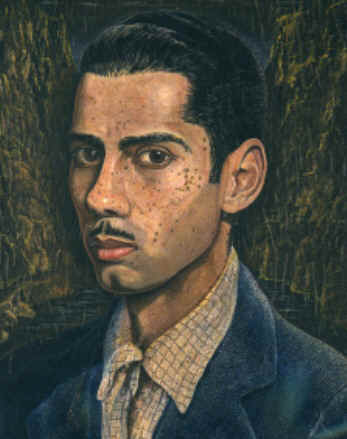

Self-Portrait

Self-Portrait

1949-1951 Watercolor on board

© Ed Clark

Collection of the artist

Clark learned at a young age that he was gifted with artistic talent. Attending Catholic school in his hometown of New Orleans, Louisiana, the sisters observed that he could copy art very well. He would draw nativity scenes and religious images by looking at post cards. As he was more talented than many of the older children in the school, he was soon put to work exercising his talents by creating scenery for school plays.

Soon after the Great Depression, Clark’s family moved to Chicago. He finished his primary education there. After performing his military service, he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago, and was told by someone there that he could go to Paris to study on the GI Bill. He arrived in Paris in 1952, determined to become a great artist. Greatness, he says, is something to which he has always aspired.

When asked why he chose to live in Montparnasse, Clark replied that he would have lived anywhere in Paris. It was by chance that he found a cheap hotel room in Montparnasse. He first settled in the Hôtel des Ecoles on rue Delambre, before settling into a top floor apartment across the street at number 22. He described this place as being dimly lit but was pleased that it had a balcony. The landlord eventually cut a hole in the roof and put in a skylight, and then Clark said that he had wonderful light that allowed him to use his apartment as a studio. His building was occupied by others who were destined to become famous artists – among them Cardenas, one of Paris’ most famous expatriate sculptors, and Sugai, one of Japan’s most famous artists.

Courtyard at 22, rue Delambre

Courtyard at 22, rue Delambre

© Discover Paris!

Clark enrolled at the Ecole de la Grande Chaumière, only a few blocks from his apartment. This school and its neighbor, the Ecole Colarossi, were very popular because they allowed creative expression that was not permitted at the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts (where several blacks also studied over the years). Clark described the Grande Chaumière as a “workshop school,” one where attendance was not taken, and students were not forced to attend classes. This was not at all like the Art Institute of Chicago, where there was constant interaction with students and work was critiqued daily.

Clark spoke fondly of two experiences there that spurred him onward toward excellence in his work. The first was a comment made by French artist and professor Edouard Goreg. Clark, who said that at the time he was determined to out paint Michelangelo, was earnestly painting a nude model. Goreg came by to examine the work and critiqued Clark by saying “this smacks of the Academy (des Beaux-Arts)”. Clark went on to relax his attempts at perfecting technique and allowed himself more freedom of expression in his painting. Goreg was to eventually judge Clark’s work at a show at Paris’ Gallery Craven in 1953, one of the rare expositions that featured American artists at that time.

Académie de la Grande Chaumière

Académie de la Grande Chaumière

© Discover Paris!

The second incident occurred when Clark decided to try his hand at sculpture. Though devoted to painting, he decided to take a class in sculpture “because it was free”. He had the opportunity to sculpt the same model who posed for Rodin’s The Thinker. Clark’s professor for this class was none other than the Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine, whose atelier in the 6th arrondissement in Paris has been converted into a museum devoted to his work. Zadkine critiqued one of Clark’s sculptures by saying “I see that you’re a painter,” indicating that Clark’s approach to the medium and the art form was inappropriate.

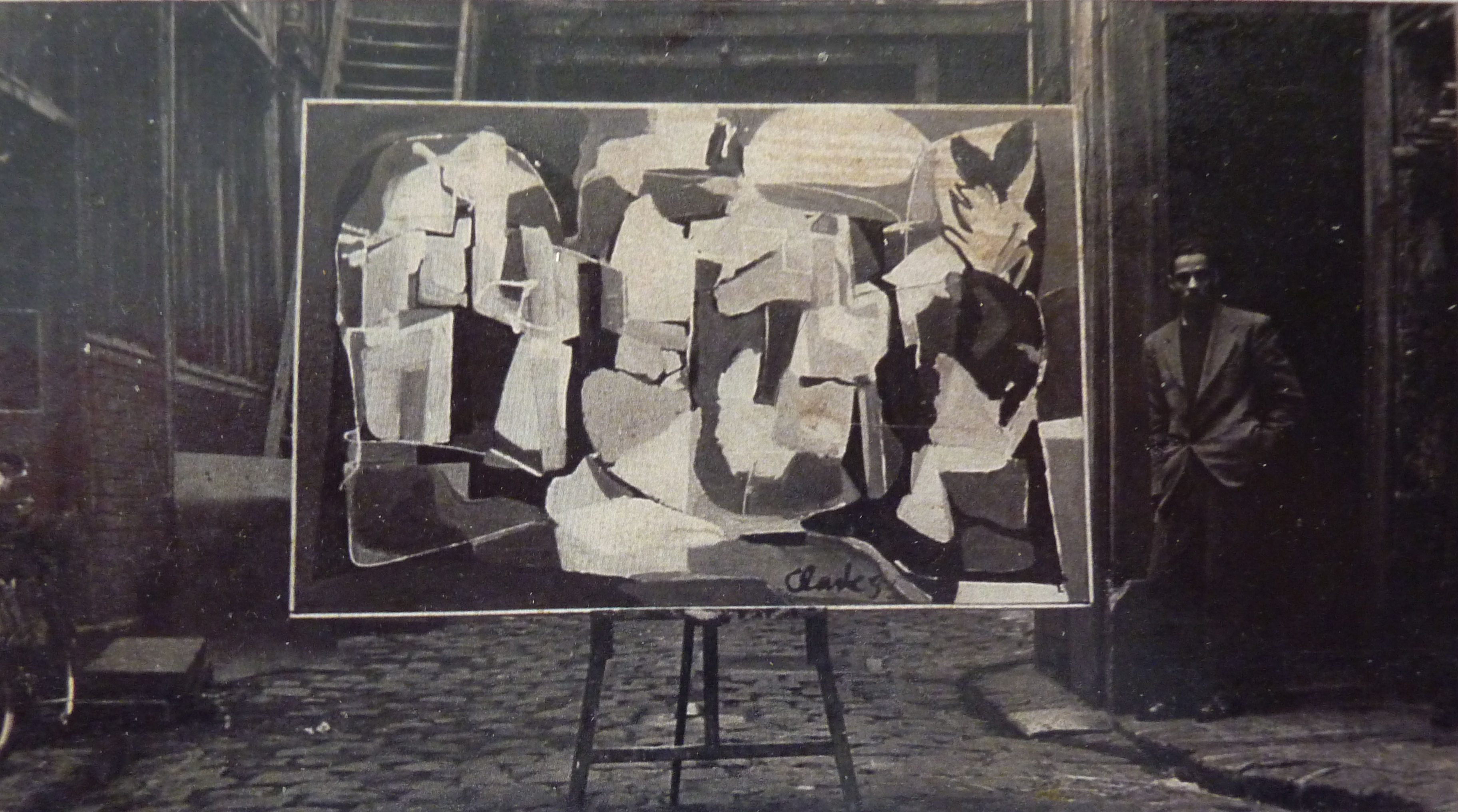

Clark describes himself as the first African-American painter to use large canvases for his work. The painting entitled The City (1953) measured 51x77 inches was his first such endeavor and was influenced by the work of Russian artist Nicolas de Staël. He exhibited many such works at the 1954 exhibition entitled Grandes Toiles de Montparnasse sponsored by the American Center for Students and Artists. In 1955, he created a painting that measured 4x3 meters (~13x10 feet), which he said was the largest painting ever made in Europe at that time.

Ed Clark and The City in the courtyard at 22, rue Delambre

Ed Clark and The City in the courtyard at 22, rue Delambre

Image courtesy of the artist

Clark’s work was reviewed by Le Monde critic Michel Conil-Lacoste, something of which any artist would naturally be proud. Given that the French took a negative view of art created by Americans at that time, the review was even more impressive. But Clark’s pleasure in this review was tainted by the fact that Lacoste referred to him as “a Negro of great talent”, a statement that could have been interpreted to mean that most blacks were not capable of having great talent. Clark had been impressed by the overall lack of attention paid to his color by the French, and so was curious as to why Lacoste explicitly mentioned his race. He had the opportunity to meet Lacoste at the Café Select (one of the four famous artists’ cafés in Montparnasse) and ask Lacoste why he had done so. Lacoste replied that he had not been aware that Clark was black, but that when he asked about Clark’s work, he was told of Clark’s race and simply reported it as a matter of fact, not of judgement. Lacoste was instrumental in getting Clark’s work into the Gallery Creuze, where he had a one-man show in 1955.

Interestingly, and perhaps not surprisingly, the Herald Tribune would not review Clark’s work. This Clark attributes to racist attitudes. While the French press might have been generally anti-American in their mind-set toward artists, the American press was definitely anti-black American. But Clark found that among American artists in Paris, the common love for art could bridge the gap between blacks and whites. He described how many white artists were lonesome for the company of Americans, and that even southerners were eventually able to overcome their prejudices and “make friends” with blacks. This would have been inconceivable in the United States.

The Montparnasse cafés (Le Select, Le Dôme, La Rotonde and La Coupole) were traditionally the places where artists gathered to socialize, share ideas and promote their work. This tradition continued during the post World War II era. Clark described one afternoon where he encountered a white American in Le Dôme who was buying paintings from many artists who were showing their work. Clark left the café to tell fellow African-American artist Beauford Delaney to bring a few of his paintings to show. The man bought paid a high enough price for Delaney’s work that Clark was anticipating having a wonderful steak dinner with his friend that evening. But instead of leaving the café to spend the money, they sat down with the man to chat with him (Clark describes Delaney as a “great conversationalist”). When the man’s bill was presented, he had no more money to pay, and regretfully asked Delaney to take his paintings back in exchange for the money he had paid. Delaney did so, and both he and Clark could only chastise themselves for not leaving earlier.

Contemporary photo of Le Dôme

Contemporary photo of Le Dôme

© Discover Paris!

At this time, both Clark and Delaney were struggling artists. Clark recounted the time that Delaney loaned him seven 5 FF pieces (he remembers this detail because the 5 FF coin had just been introduced as French currency), and just how significant that 35 FF loan was to him. He also told of visiting a friend at his apartment where several others were also visiting. It was only when everyone else left that his host could offer Clark refreshment, as he could not afford to do so to everyone. So the disappointment experienced when Delaney gave up his fee at the Dôme was heartfelt.

When asked whether or not there existed a true African-American community during his years in Paris, Clark said that there was definitely contact among blacks in Paris at that time. He spoke of the Café Tournon where Richard Wright, Chester Himes and Ollie Harrington could often be found, Haynes’ restaurant, and artist Herbert Gentry’s club in the rue Jules Champlain in Montparnasse. But he said that the artists and the writers mixed with other races as well. Clark says that his best friend to this day is Bob Shigeo, a Japanese-American who he met during his Paris years. Shigeo was also a friend of Beauford Delaney and African-American journalist Richard Gibson.

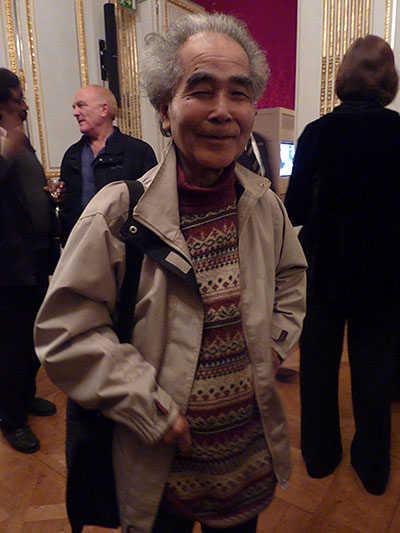

Bob Shigeo

© Discover Paris!

In talking with Shigeo, who still lives and works in Paris, one gets another perspective on the art world of this era. Shigeo attended the Chaumière with Clark, and also the Ecole Colarossi. As did Clark, he came to Paris on the GI bill, and attributes the advancement of civil rights in the U.S. in part to the fact that African-Americans and other minorities took advantage of the bill to travel abroad and experience a liberty that was not known to them at home. He vividly describes the art exhibition scene in 1950s Paris – it was much less expensive to produce promotional materials and exhibitions were much more a creative exercise than a commercial one. To get press coverage was a sociopolitical game however. According to Shigeo, this remains true today.

Because of Clark’s fondness for a new-found lifestyle and the French capacity to “live and let live”, and also because of the success that he enjoyed with his first solo exhibition, he stayed in Paris after his GI benefits were depleted. But he ran out of money after the commercial failure of his second show and moved to New York with a group of artists to create a co-op avant garde gallery. Like the Herald Tribune in Paris, the New York Times and other papers declined to review his work.

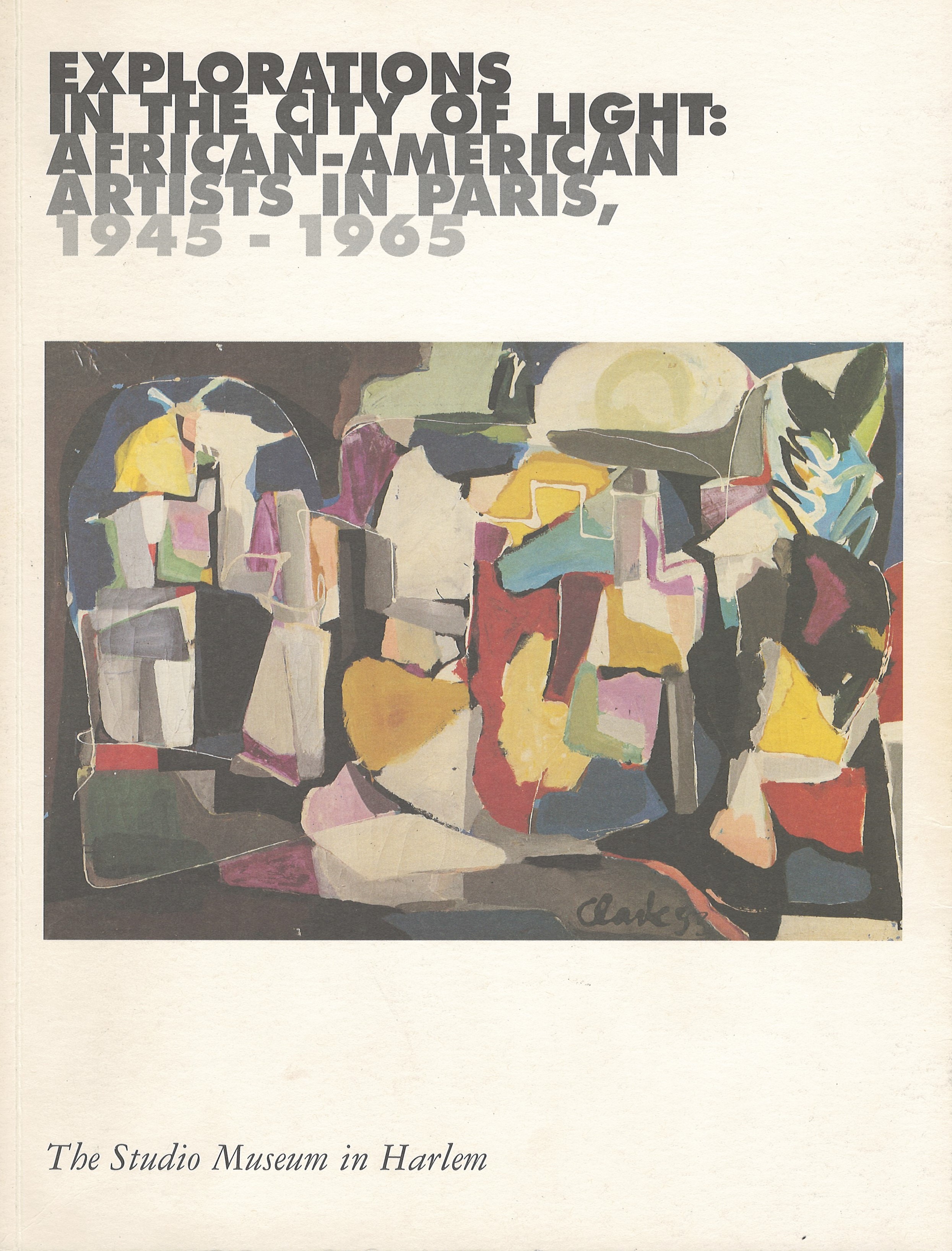

Clark returns to Paris almost every year to paint. He credits his appreciation of the use of natural light, so important to the Impressionists, and of color to his training in Paris. He has had numerous exhibits in Paris since the 1950s. He is also proud to say that the late African-American multimillionaire Reginald Louis and his wife Loida, residents of Paris, own 12 of his works. Clark was one of the artists featured in the exhibition entitled Explorations in the City of Light: African-American Artists in Paris that traveled throughout the United States in 1996-97.

Catalog cover for Explorations in the City of Light

Catalog cover for Explorations in the City of Light

Living in Paris and traveling throughout France gave Clark a different perspective on artistic expression. This deeply influenced his approach to painting. He says that he would freely advise young artists to come to Paris “not for training (as I did), but for life”, but would warn them that it is hard to earn a living there.

To sum up what Clark has learned from his Paris experience in relation to his work, he states emphatically “Art must be more than correct – it must be beautiful!”

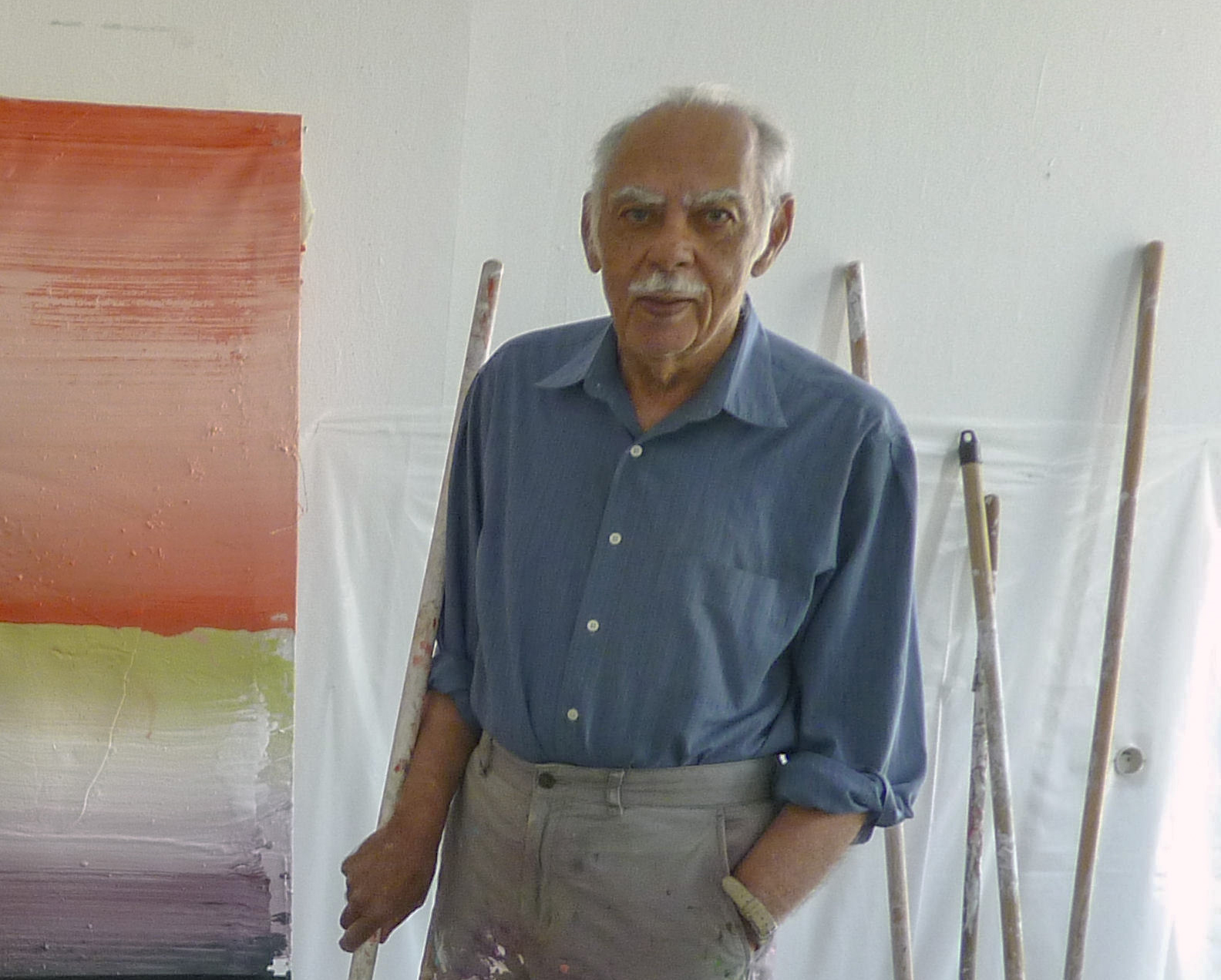

Ed Clark at Cité Internationale des Arts

Ed Clark at Cité Internationale des Arts

© Discover Paris!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!